Novices and accomplished writers alike seem to agree that writing is hard. One would be a fool, then, to pass up on hard won insights from an author of twenty novels, and the winner of the Booker prize and the Booker of Bookers prize. Salman Rushdie Teaches Story Telling and Writing, a 19 part seminar on the art and craft of fiction writing produced by MasterClass, comes with an 18 page booklet with Rushdie’s bibliography, his influences, a reading list, and brief notes on magic realism and the craft of outlining a novel. Salman Rushdie’s tips for writing and storytelling cover the essential and the idiosyncratic aspects of fiction writing, and are definitely worth the perusal of those called to the vocation.

Here are some nuggets from the 4hr17min masterclass.

The Delphic maxim know thyself is a good tip to live by for the general public, but also a prerequisite for writing well. A lot of the skill of the writer comes, says Rushdie, from “your understanding of who you are and what you need to say to the world.” While nobody reads nowadays people hoping to become writers really ought to. You don’t need to audit a Rushdie MasterClass to know that “most writers are born out of readers.”

If you feel the need to pursue writing then be warned that “it doesn’t come easily.” But also remember, when you succeed in expressing your ideas: “it is an incredible exhilaration.” Your writing is an expression of your deeper self, a book is your take on the world. So, to write with confidence you need to be clear about who you are. If you believe in your writing, you’ll be able to draw on that resource as a source of comfort before you make it. Writing is not an easy career, and even successful writers suffer from bouts of anxiety, self-criticism, and self-doubt at the start and end of a project. Rushdie was not at all confident about the performance of his first major book Midnight’s Children, though he was confident he’d done the best work he could at the time. If he were put in the position again, and asked to dedicate thirteen years to a project that might or might not come off, he says he probably would not even try. Having crossed that hurdle, and made a grand success of it, he observes “if you want it to come easily, then, you’re probably in the wrong line of work.”

Developing a sustainable relationship with your writing involves being at peace with fallow periods. Rushdie advises writers to keep at writing even if they’re only managing to write trash; eventually, he says, something will stick. The germ of an idea which persists can turn out to be the thing that grows into a new book. If you learn to trust the process you will find a lot of fragments tend to generate ideas which are workable.

Read Widely to Write Well

The vast majority of readers are parochial in their reading habits; preferring books about people like themselves. Writers are doing themselves a disservice if they don’t read books not originally written in English, and featuring people very unlike themselves. One of the powers of literature is its capacity to bring into relief the similarities between different peoples, the common human factor underlying the observed variety in regional cultures.

As Rushdie notes, the cultures of Latin American countries and South Asian countries though patently very different are conditioned by their colonial histories under Spain and England respectively. They also have in common a stark urban-rural divide, military interference in government, and dictatorships. Many Latin American writers credited with founding the magic realist movement in writing say they took their inspiration from One Thousand and One Nights; a book written in Persian, which was translated into Arabic, then French, then English, and then almost every other language. Rushdie, also often called a magic realist writer, was hugely influenced by the works of Latin American writers. This goes to show that for writers there is a lot to be learned from reading outside one’s cultural tradition.

Plot Structure

Having a good sense of the plot will allow you to know where “to hang your hat” when you’re deep into the process of choreographing tens of characters through hundreds of scenes. While the Aristotelian saw that stories must have a three part structure, with a beginning, a middle, and an end, is as frequently recommended now as ever, understand that your story needn’t have them in that order. “The only rule is whatever works,” says Rushdie who has relished Joyce’s Ulysses, all of whose events occur in the span of a single day, and the movies of Truffaut which cannot be made sense of in terms of that tripartite structure. You could start at the end and trace back through the middle to the beginning, or start in the middle and end right there, or come up with any combination of these elements. You could well write a story about a single moment.

Allow your story to unfold. Often the story will suggest its own ideal structure as you write it. “The story will tell you what it needs to be.” Most importantly, notes Rushdie: “A novel can be anything you make it as long as it is not random.” Things need to happen in the novel due to their own internal logic, but there is no need for that logic to be as predictable as the three part structure suggests.

The Elements of Plot

Stories are fundamentally about who does what to whom. In a big book with a large cast and a big number of scenes, the destinies of individual characters will not connect with each other. But, parallelly, observes Rushdie, “if the novel has a smaller frame then the destinies of the characters are absolutely interlocked.” When there are many characters separated in location and time, it can be hard to create a sense of cohesion in the novel. To address this problem he recommends the use of the device of “mirroring.” If you have one set of characters having one sort of conflict at one time and place, you can try having another set of characters at a different time and place having a similar conflict. It needn’t be the same conflict, and needn’t be resolved in the same way. In fact if the mirroring is too perfect, too pat, it will come across as contrived and unconvincing. Suggest, for instance, suggest a loose similarity between two cads, or victims, in different parts of the novel and the reader will make a connection between them though they are separated by time and location in the narrative. This sort of mirroring will also give the novel a cohesive structure and allow the reader to see its unity in terms of the form.

If the foregoing seems to demand more systematicity, and preparation before writing, than you have the stomach for, be advised that Rushdie thinks trial and error is an equally legitimate way of concocting your yarn. “Embrace the false starts,” he says. If you keep working through the false starts till you arrive at an attractive place then you can get a solid story out of what looks like a haphazard process at the outset. Of course, it can take many attempts to arrive at the entry point best suited to the story you want to tell. It took Rushdie over five years to write The Satanic Verses. Partly, because it is composed from ideas that were originally intended to be themes for three separate books. One a book about Indian immigrants in London, another more visionary book about angel-devil nightmares, and a book about childhood. Systematicity is onerous, but going in with an underdeveloped plot can bring its own challenges when you try to unite the various strands of story you’re itching to tell.

The Extraordinary Power of Opening Lines

The opening line does double duty, says Rushdie, in that it tells the writer how to go on and tells the reader what to expect. A good opening sentence will tell you what the next couple hundred sentences ought to be. If you know what the book is about you’ll find it a lot easier to come up with a suitable opening sentence, one which “shows you how to write the book” and tells the reader why they may “want to read on.” While the opening sentence is the first to be read it often won’t be the first you write. Sometimes the best opening sentence might be one that you write when you’re far along the story arc in a scene that comes much later in the narrative sequence. If it is a revelatory sentence, one which captures the vibe of the book, consider moving it to the start even if it means you’ll have to adjust the sequence of scenes. It is worthwhile to give the reader a condensed view of what you mean to be doing through the rest of the book, and a good opening sentence can do that job admirably.

Always try to tell the reader what sort of book they’re embarking on very early in the book. “Start as you need to go on.” “The worst thing you can do as a writer is to make the reader a promise about the sort of story you’re going to tell them and then not tell them that kind of story.” This applies not only to opening lines about also to the preliminary question about the genre of book you’re writing. You mustn’t start realistically and then suddenly change into a fantastic style. If you’re writing a highly imaginative book you must think about the departure from realism, the liberties you want to take, before hand and then write accordingly. Begin your magical story in a way that clearly establishes that it is a world where that sort of magic is possible.

Matching the Story to the Appropriate Register and Storytelling Devices

“A big car needs a big engine,” says Rushdie. But if your car, i.e. your story, is a small one you still need to know:

Whose story are you telling?

What is the story?

Why are you telling the story?

When and where does the story take place?

How will you tell the story?

Answers to these questions will tell you how to go on, what aspects you will draw attention to in the story that someone else would not, what you know about the characters that other’s don’t in the narrative universe, how you will convey a sense of location and time, and whether you are telling a tragic or comedic story. For Rushdie it is “story that puts the vroom vroom factor that drives the book.” One way to make sure you’ve got the general shape of the story down is to try to write the story as you would verbally narrate it to a friend. Alternatively, write a letter to yourself where you outline the story as to a friend. If the story makes sense in this form, you’re good to go.

Creating Convincing Characters

Traditionally, stories worked on the idea that characters’ lives end up a certain way because of the way they are. The old chestnut that character is destiny has cast a long shadow on story telling in the Western canon. But, Rushdie is emphatic: “character is not destiny.” “Our lives can be changed by things we can’t affect.” Victims of a terrorist attack, for instance, don’t end up maimed or dead because of their character but because of the thoughts and deeds of people they don’t know. So, feel free to have good things happen to bad people and vice versa. Your characters will be more lifelike.

It can be hard to invent convincing characters whole cloth. An easy solution is to base them off of someone you know very well: yourself. You can base a character off yourself, and introduce small and big differences as you go along. But beware there comes a time when a character develops a personality all their own and then you have to listen to the character. “Once you’ve made the character you have to respect who the character is,” admits Rushdie who has tried and failed to make passive characters dynamic.

Rushdie asserts that “anybody can write about anything. Because if that’s not so, then, nobody can write about anything.” This is bad philosophy because the negation of “anybody can write about anything” is not nobody can write about anything but some cannot write about some things. Nevertheless, it is a good bit of rhetoric which serves as a motto for the writer afraid of the task of inventing convincing characters. Your job as a writer is to write about a good many people quite unlike yourself. It’s salutary to remember that writing fiction is “a little like reportage.” You can draw on real life figures to give personalities, quirks, and even allusive power, to your characters. Don’t appropriate public figures as you find them, but take bits and pieces you can use.

Writing about unsympathetic characters, people with “a likeability problem,” is an interesting challenge. You can learn from the model Nabokov provides with his provision of the vile pedophile Humbert Humbert as a narrator to accompany us all through Lolita, or George Elliot’s placing the braggart and bore Edward Casaubon at the heart of Middlemarch. Learn from the models how to write unlikeable, unsympathetic characters who can nevertheless compel the reader’s attention, and possibly even exercise their empathy.

At a certain stage of writing the characters come alive and when you listen to them it allows you to write characters that don’t look like puppets to the reader. Determining their behavioural and verbal tics, understanding their interiority, and thinking seriously about how they interpret their world is “valuable and necessary.” The exterior aspect of characters is important too. It is easy to start with how they dress, or how they present themselves to the world, but this can give clues to their interior life as well. You shouldn’t write fiction “unless you can hear [the characters] speak.”

Expositing Character

What’s special about your character? Dialogue, interior monologue, and action, are three vehicles you can use to reveal your character’s selves. Dialogue must be sensitive to the story; you have to understand what role it is playing in the story. A slice of life story needs authentic sounding dialogue. But a novel of ideas needn’t be limited to realistic dialogue. Every Don DeLillo character speaks like Don DeLillo. Every Raymond Carver character, by contrast, speaks exactly like they would if you met them in real life.

It’s a good exercise to write a dialogue scene with a couple of characters where people can tell who is speaking without being told who is speaking. If the dialogue and narrative can achieve “differentiation,” where each character sounds different from the other based on how they act, speak, and think, then they can “exist on the page without you having to spell it out all the time.”

Ink portrait by Cain S. Pinto (2011)

Setting as a Character

Describing the location well will help clarify the kind of story being told. If you’re telling a story about the immigrant experience, for instance, it matters how well you evoke the homeland and the adoptive domicile to convey the lived experience of the immigrant. To write effectively about locations try writing about the significance of some place for yourself. If you are able to capture the specific significance a place has for you in your writing that will help you avoid clichés. One exercise to avoid writing in clichés about locations is to write about the place without the use of any adjectives; this will force you to tell a story.

The same place changes over time. So you need to be careful about what has changed over the last fifty years and what might change over the next fifty years. The same place would appear quite different in the past, the present, and the future. For instance, writing about New York in the 70s must not have the World Trade Center, but the Met Life building; in the 90s there must be a mention of the World Trade Center. Iconic locations in the place and time your narrative is set are crucial for setting the atmosphere of the scenes that are part of your story. If the sense of place is conveyed well the story will be all the more convincing viscerally.

The feelings a place evokes will make the place more vivid in your writing. They can equally well be negative feelings, or positive feelings. It is the intensity of feelings, rather than their valence, which translates into the writing. “If there are half a dozen moments [with a visual element] in the book that the reader can’t get out of their head then it is a good book,” advises Rushdie whose writing is as influenced by cinema as it is by literature. Dramatising the non-verbal requires good visual writing pace writers who think writing is a purely verbal enterprise.

Your Unmistakably Unique Worldview

A novel is essentially just your take on the world. In learning about yourself through writing “you can’t be easy on yourself…it’s like a deep psychoanalysis,” warns Rushdie. A parallel with reportage suggests itself in the fact that different news outlets, different journalists treat the same facts with a different lens. The interpretation of facts in the narrative world, likewise, calls for the editorial vision of the author; the writer gets to convey if a man slipping on a banana peel is funny or tragic, for instance, based on how they chose to portray the man and the circumstances under which he happens to step on the banana peel.

It’s good advice to write what you know, but you must “increase what you know.” If what you know is not interesting, maybe, you need to do more research and learn something that can be interesting in your narrative universe. You can’t keep writing about people like yourself and the people that surround you without ending up repeating yourself and showing yourself to be a one trick pony. There are exceptions, like Faulkner who only lived in Mississippi all his life and managed to write about people like himself and also people very unlike himself with great insight and moral conviction. But you can do worse than learning to see the world through other’s eyes by undertaking first-hand research. Travel is one way to do this.

“Travel alone. If you travel with someone you carry your world along.” Subject yourself to surroundings, situations, and beliefs unlike anything you are familiar with and don’t hide behind the company of familiar companions, comforts, and rituals. If you immerse yourself in the lives of those unlike yourself you’ll be able to write about them in an authoritative, viscerally true, way.

Negotiating Influence

“All writers have influences,” observes Rushdie. But imitation can be harmful. It can get you going, but you must be able to go beyond and write like yourself. Imitation will only produce a lesser version of the original. Journalistic research can be a good way to learn enough about an issue to write authoritatively and persuasively without falling back on tics you’ve picked up from your literary heroes. By using what you observe in your fiction you’ll be able to write setting and character persuasively. You’ll avoid falling into the trap of describing places and people like your literary heroes do. You could also invent your descriptions, but inventions can run afoul of what things really are like. If you make up something based on poor research and guess work people will call you out, and you’ll “deserve it” warns Rushdie.

“You should be a good noticer,” he says. If you actively observe, listen to people speaking without them knowing they’re being heard you’ll find things you’d never be able to invent. The vibe you get off a street, or a house, can influence the way you describe it. To be able to capture a mood you should have a good sense of how it comes across to you. It’s easy to take in snapshots of the world in blindly, based on what we’re paying attention to, without getting a sense of what it all suggests. A house with a prominent bookshelf suggests that the occupants are readers, or that they’re poseurs who’ve bought books by the foot to give others the impression that they’re readers. In either case the bookshelf is communicating something. Be observant.

Developing your Narrative Style

Rhythm is a vehicle of meaning. Rhythm can convey meaning subliminally. While creative writing courses can be very good at teaching craft skill they are not so good at individualizing the voices of different writers. People who come out of a creative writing course tend to sound the same. “Everyone coming out of class tends to write the same way” rues Rushdie. Style and voice are imprecise terms. But you can think of the former as being the degree to which you stick to or depart from classical form and the latter as what makes a piece of writing uniquely your own. A lot of MFA programs churn out writers who can write in classical style about how their dad doesn’t get them, their mom doesn’t love them, and the girl they’re infatuated with doesn’t notice them. If only one of them wrote about how when they were ruing the fact of passing unnoticed by a love interest a flying saucer landed in the garden their work would be much more interesting.

“Read Strunk & White”, understand how to write in that style, and then go ahead and do what you think is necessary to tell the sort of story you want to tell, says Rushdie. But you can’t just stick to that classical style for everything you write. The work of fiction has a certain autonomy. It is a subject-sensitive autonomy, and you have to let the work decide which style is most fluent and natural in the telling of its story. “Don’t think about it as being about you, [but] being about what you’re writing…[otherwise] ego intrudes.” Style is about finding the right fit between register, cadence, vocabulary and subject matter. “Nabokov’s style is slightly show-offy,” but Doctor Seuss writes in a very basic vocabulary. Dr. Seuss couldn’t have written Lolita, and it is doubtful Nabokov could’ve written Green Eggs and Ham. The rhythm of the sentence is important, and you need to try to match the rhythmical quality of your sentences with what you want your sentences to communicate.

Writing Surreal Stories

All good writing is in the business of truth telling says Rushdie. Fantasy and social realism can both be used to tell the truth, what we can call “human truth.” They can both be effective, but they have their own rules of composition. Surrealism isn’t confined to the real world but is most effective when it is close to the “emotional truth.” If you intend to tell a surreal story the fantasy element “must be part of the initial concept of the story.” You mustn’t start realistically and then suddenly segue into a fantastic style. You must think about the departure from realism, the liberties you want to take, before hand and then write accordingly. Begin your magical story in a way that clearly establishes that it is a world where that sort of magic is possible.

Surrealistic writing always runs the risk of “silliness.” “Sometimes it just sounds dumb and readers are very, very sharp about that.” If you write something that is silly, “indulgent and foolish” you can count on it that it will not go unnoticed. It takes some experience with reading good surrealistic writing to develop the ability to avoid silliness. But one rule of thumb is to “stick close to the emotional truth of the moments.”

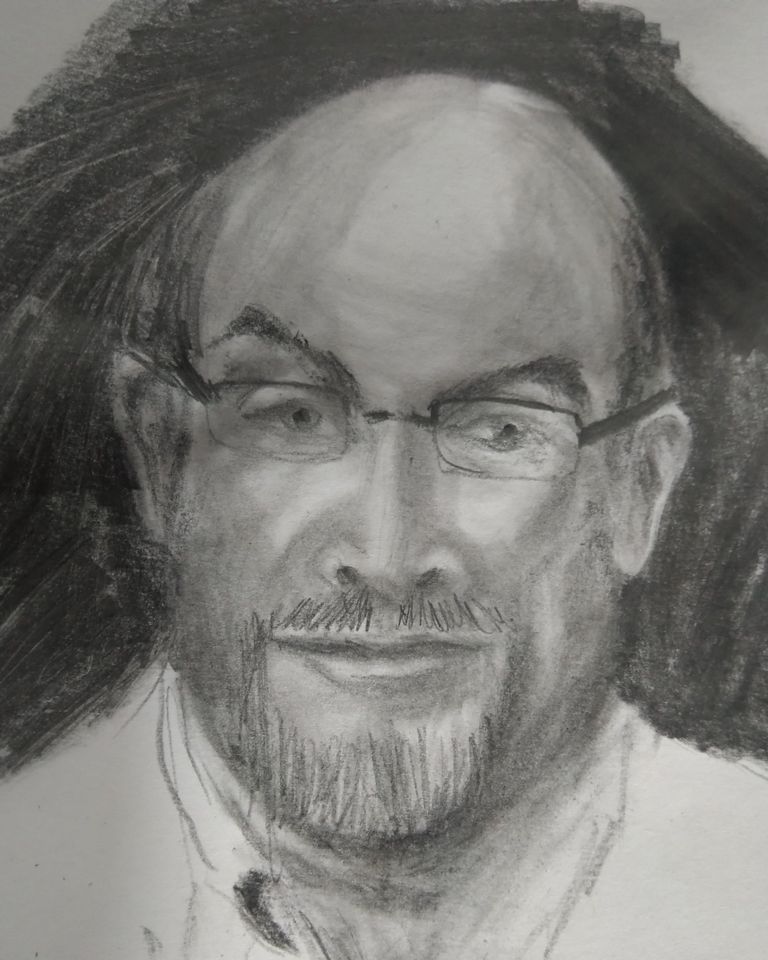

Pencil portrait By Cain S. Pinto (2022)

The Role of Research

“Writing the book is like an education that never ends.” If your novel is set in the past then its characters mustn’t think, act, and live as your contemporaries do. Your task is to be honest about their differences while building a narrative world where they are empathetic and can be related to by your contemporaries.

If you’re writing about great historical figures then you’ll have to draw on research about them. But be careful about not just rewriting them based on that research; use your own imagination, and some introspection to come up with your version of that historical figure. Your Ashoka, for instance, ought to be different from the various historical accounts about him that you consult in order to get a handle on the kind of man he was.

Google search results are very broad but not very deep. The best place for historical research, especially into the lives of ordinary people in the past, is books. It’s easy to find information about events, rulers, and wars but “much harder to find out…how ordinary people lived. That requires digging.” Be prepared to crack open good old fashioned books if you want to get into the nitty gritty of the lives of the vast majority of people in any historical setting that is not too close to the present. But, warns Rushdie, “no matter how exhaustively you’ve done the research. There’s a time you’ve got to put it aside and make it up.” If you can’t, won’t invent, your work will be the poorer for that.

All Writing is Rewriting

Your first drafts will likely be imperfect. That’s OK. The hardest part is just having written something. Merely having overcome the terror of the empty page, having put something down, will enable you to exercise your critical judgement and begin the process of improvement. You can get a long way towards improving your first draft by identifying places where you’ve said too little and where you’ve said too much. Just with these two guidelines you can get a fairly objective assessment of your writing and become your own best editor.

Always reconsider your language and your characters. You may find false notes in some passages, and rewording them can greatly improve their quality. You may find some characters are superfluous and removing them does no harm to the story. Alternatively you may find some peripheral characters become very interesting and important as the story develops. That’s a good sign, says Rushdie, and can mean that the book “has taken on an organic life of its own…it has grown, it tells me [you] things.”

“Revision is everything.” Having the whole book in its initial form finished in front of you will often trigger realizations about what needs to be different. The finished book will often tip you off about what you needed to write more about and what you need to have less of. You can use these insights to guide the process of revision. Alternatively you can fix things all the time during the writing process. At the end of the writing day do something else and come back to the manuscript. Re-read all you’ve written to identify issues of overwriting, underwriting, false notes, or alternative scenes. Make changes if necessary. If everything is fine you’re still better off for having re-read the work because the next day it’ll all be in your head and help you go forward.

If you’re writing a big book with many characters and locations, after finishing your book at a certain moment the map of your book in your mind disappears. At that point “it becomes very dangerous to revise it…like performing brain surgery blindfold or wearing boxing gloves.” At this stage it is best to accept the book as it is, warts and all. Try to do all your major revisions before your book has reached its final state in terms of narrative. Once you’ve reached the finish line, be wary; you may not be able to move things around without mangling the plot-line in unforeseen ways.

“If you can’t tell when it’s not good…you can’t really tell when it is good,” warns Rushdie. The way to develop a sense of when writing is bad is to read a lot of good writing. There is no shortcut: the more you read the better honed will be your instinct for identifying good writing. There is a parallel here with philosophy, where the key insight is that if your system cannot identify mistakes then it cannot identify truth; the intelligibility of error is a necessary condition for achieving genuine knowledge.

Sharing your Writing

If you’re feeling apprehensive about sharing your writing with someone it probably isn’t ready. “Embarrassment is an infallible test,” says Rushdie. Writing is a solitary process but it ends with a product you want the world to see. When the work is good, you won’t feel embarrassment about sharing it. You’ll probably be eager to have other readers look at it. But remember you want people who will tell you the absolute truth, not people who will gush and say you’re awesome. Even if your writing is awesome getting that feedback is not very helpful. Readers telling you what worked and didn’t work for them while reading your manuscript will give you the best guidance. You shouldn’t coach your early readers. Let them read and see what the book says to them; if it does that job, you’ve succeeded but if it doesn’t it probably needs more work.

A good editor is someone who wants to make the book the best it can be, not one who wants it to be another book. The best editors will tell you where the problems are without telling you how to fix them. Develop a good relationship with an editor who tells you what might be problematic and gives you room to find the best solution. You know your story, your book, better than any editor. So, consider what they say carefully but don’t make changes you’re not convinced are necessary. If many editors give you the same feedback, it might be that the work may benefit from fixing the issue they’re singling out.

Salman Rushdie’s Listicle for Aspiring Writers

1. Determine if you’re a minimalist or a maximalist, want to write books about a simple story or a story about everything.

2. Figure out if you are temperamentally a planner or an improviser. Work accordingly.

3. Only write a book if you can’t help but write it.

4. Take creative risks.

5. Don’t get up without getting some work done.

6. Often the best way to solve a problem in a story is to discard that problematic bit.

7. You won’t be a writer until you finish a book.