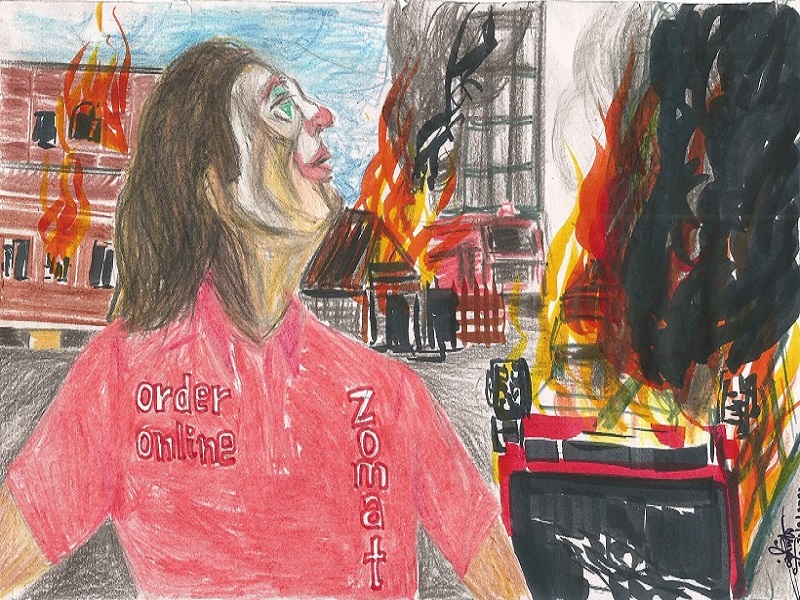

In the last few months, there has been one story too many on the allegedly low income of Swiggy and Zomato delivery partners. Many have taken to social media to express their shock at these earnings and their outrage at the meal-delivery platforms. The mass sympathy that has poured is bewildering in light of the average income in the country as well as the typical salaries and daily earnings of various professionals, semi-skilled and unskilled labourers.

This article by Entrackr is typical of the recent coverage. Here the monthly income of a delivery partner calculated based on the data he provided is INR 23,400. The ‘net’ of INR 10,900 has been arrived at after subtracting expenses including rent, electricity and fuel costs. However, in calculating how much a partner is earning from the company, it seems fair that only costs incurred in order to carry out the job be deducted. Here, when fuel charges of Rs 6,500 are deducted, he is left with 16,900. Other delivery partners have stated that their real earnings in recent months have been closer to INR 10,000. According to Inc42’s analysis, delivery workers are earning a gross income of INR 15,000 to 20,000. According to Zomato, the top 20% of its riders work over 40 hours a week and earn more than INR 27,000 a month.

Before making the case for higher pay or declaring these workers exploited (on account of earnings per month alone — this article is not about other working conditions or the alleged use of algorithms to prevent workers from reaching their targets), it is worth asking what the appropriate earnings should be for a job where the skills required are the ability to ride a bike or scooter, and the very basic education needed to operate a mobile App.

The per capita income in India in financial year 2020-21 was USD 2,227. Per capita net national income (NNI) was INR 126,000 or INR 10,500 per month. Many of the entry and even mid-level salaries of white-collar workers are only as much, sometimes lower than the monthly earnings revealed by Zomato and Swiggy delivery partners. This includes industries like engineering, IT, media and banking, among others, where personnel have technical or other skills as well as a higher level of education than the average Zomato delivery partner. According to Glassdoor’s data, the average salary of customer service workers is INR 18,000 a month; of a medical assistant is INR 20,552; of a pharmacist is INR 19,400; of a phlebotomist is INR 16,474; of an office assistant is INR 23,795; of a nurse practitioner is INR 25,496. According to Monster Salary Index Report 2019, the Education and Research sector scores the lowest wages, with a gross hourly wage of INR 139.7, even lower than the logistics sector. By protesting against the ‘low earnings’ of Zomato and Swiggy partners, are we saying they should earn as much or more than these professionals? If we are, then we should come out and say so in so many words.

Zomato and Swiggy, like most corporations, are easy targets for noisy individuals who imagine they are achieving social justice by ordering pizza, tipping their riders, tweeting about it, plus for good measure complaining about how the companies creating jobs are the worst. Many cannot be bothered to consider the larger social and economic problems India faces, nor even the fact that they might easily find more deserving (that is to say, worse off, more exploited) subjects for their sympathy if they were to pick a random person from the population by lot. The fact that middle-class city-dwellers come face-to-face with food delivery partners on a regular basis, as opposed to construction workers or other labourers whose earnings they don’t have to contemplate, probably compels them to relate to delivery men and their struggles. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Though the particular affinity the public seems to have these days for meal delivery workers can easily become a case of political correctness gone mad, as it probably was earlier this year when a Bengaluru woman alleged a Zomato delivery worker punched her in a disagreement over a late delivery, while he claimed she hit herself with her ring. Despite the statistical likelihood of ‘man punches woman in face’ being sadly far, far greater than ‘woman hits self in face with ring, breaking nose,’ the consensus online was that the woman was lying. The confidence was terrifying. Dislike for the (relatively) privileged irate woman trying to get a free meal after a late order and sympathy for the poor working man reduced to tears brought out everyone’s ugly sexist side, however else they may try to explain it. Despite no real evidence for her guilt, there were people demanding she be fired from her job, banned from platforms, etc. It appears grievance theoretic armchair social studies and the culture of cancelling people over Twitter have finally arrived in India.

Sympathy for anyone should not become grounds for unreasonable demands. And demanding that unskilled/semi-skilled labour in large supply be paid the same as or more than skilled labour, especially by companies that are strictly speaking loss-making enterprises, is unreasonable.

The angst riders feel is probably justified insofar as it concerns false or misleading information provided by the companies looking to hire them, and the difficulty they face accessing managers to resolve disputes. As for the drop in earnings compared to earlier flusher times, this a grouch gig workers have consistently voiced, including Ola/Uber drivers. Here is a problem of misplaced expectations on the part of drivers/riders, as attractive incentives on joining were probably not meant for the long run nor would they have been sustainable. A failure to appreciate the limitations of the business model of the companies they had signed up to work with led to disappointment at best, and financial loss at worst, like in the case of Uber fleet owners who made a business out of buying car after car and hiring drivers to drive for them. In these types of arrangements, one never hears of the actual driver complaining to the cab owner about his wages being too low. Similarly, one has overqualified Swiggy and Zomato riders previously working jobs paying on average INR 20,000 a month, who found delivery work more lucrative when it was paying up to INR 40,000 to 50,000, but not any more when rates have come down.

Market-driven economies must be made of market-driven businesses, as is the case with Mumbai dabbawallahs who earn roughly 12,000 a month (less since the pandemic). Here, each meal-delivery worker delivers about 25 to 30 lunch dabbas a day (and the same number of empty dabbas back home), cycles being the mode of transport to and from railway stations. The willingness of families and individuals to pay a certain rate for the pick-up and delivery of home-cooked meals and the willingness of dabbawallahs to provide their services at that rate are the forces determining how much they earn. Why should it be any different for Zomato and Swiggy delivery partners?