Rating: 3.5/5

Charlie Kaufman’s (2020) Antkind has been described as unsummarizable. Though he has offered an intelligible gist in several interviews, it’s fairly obvious he doesn’t want readers to think that’s that. The teeming mass of characters and events animating the novel, endowing it with thematic density, can be construed as peripheral to the central plot recounting the many trials of the protagonist Balaam Rosenberger Rosenberg as he tries to bring a 3 month long stop motion animated movie 90 years in the making, started in 2006 and completed in the 1926, by deceased psychotic savant director Ingo Cutbirth to the world’s attention. The only existing copy of the movie is destroyed almost entirely when his car catches fire, and Rosenberg struggles to recreate the plot of the movie from a single surviving frame through the rest of the novel. It is hundreds of pages before the reader unfamiliar with Kaufman’s oeuvre can make an educated guess about the fate of this archival project.

Inter alia B struggles to earn his filmmaker daughter’s respect while giving her movies scathing critical reviews and dumps unsolicited mansplanations anonymously on her blog’s comment section. Donald J. Trump, deliberately poorly disguised as Donald J. Trunk to avoid legal liabilities one presumes, becomes enamoured with robot technology and commissions a whole family of bionic Trunks and an army of Donald J. Trunk clones which take on a fast food company, Slammy’s, attacking him and his policies in their commercials. This topical bit, now obsolete under Joe Biden’s presidency, is a chore; it would be so even if Trump had retained the presidency. The reader is subjected to an endless barrage of paraphrased and repurposed Trump tweets, interview quotes, and Trumpisms which lose their entertainment value fast. Kaufman may think these are the best, like you wouldn’t believe, I assure/can tell you. But are they really? The funniest Trunk incident, for what it’s worth as a digression in a sea of digressions, is his having “great sex, the best sex…No homo…Keep America great” sex with the Trunk lookalike robot whose resemblance and fuckability sell him on the potential of robot technology. Kaufman fans and critics will likely agree he has a penchant for the shaggy dog story form. But he doesn’t coast on the strengths of that gimmick alone. In enriching the set-up of premise→discursions→anticlimax native to the genre with richly suggestive subplots, empathetic character development, and a welcome disrespect for writerly conventions, deftly moving his audience across the full range of human emotions, he shows himself to be a veritable shaggy dog whisperer. The quintessential Kaufman plot is peopled by “lonely, neurotic” characters who set themselves, or find themselves captivated by, a grand task which then becomes their raison d’etre. The narrative propels them by turns tantalizingly towards and frustratingly away from their goal till a momentous anti-climax shows the whole enterprise to have been ill-starred. Think for instance of Caden Cotard in Synecdoche, New York. He sets himself the task of theatrically depicting and celebrating the everyday reality of New York in such detail that the set becomes indistinguishable from the city; cast, crew, and Cotard along with their respective doppelgangers live out their lives on the sets. Cotard’s disintegrating personal life can be told from his play acted life, if barely, only when hearing his appointed director’s cue ‘Die!’ he promptly dies in the arms of an actress playing his mother.

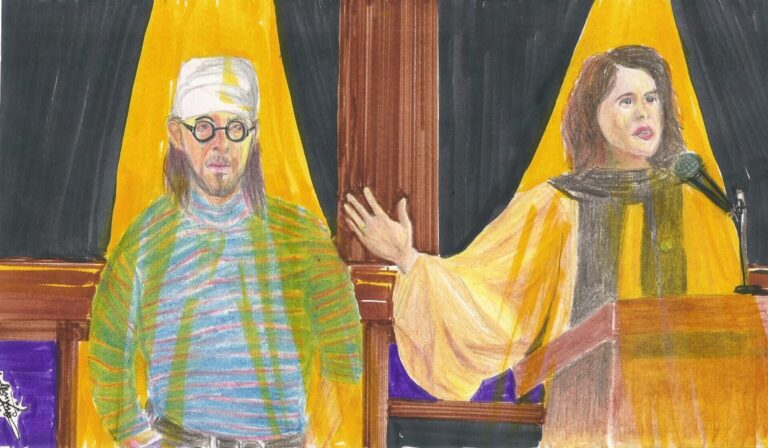

A preoccupation with the perils of identity, his own and other’s, drives Balaam to go by the initial B which conceals his gender as well as his religious affiliation, and to use the pronoun “thon”—a neoterism proposed by Charles Crozat Converse in 1851, who surprisingly goes uncredited by the omnilegent Rosenberg. B wields his, no thons, glabrous pate and deliberately ungroomed beard unabashedly to communicate thon’s disregard for conventional beauty standards. Thon hopes to be seen as morose and dejected, and consequently as a brooding genius. Thon’s dreams of childhood in which thon is “just not smart enough” worry thon because thon spent thon’s youth trying to explain away thon’s poor scholastic performance as a consequence of being an “artistic type, full of daydreams and poetry and deep sadnesses and vim and a rebel’s love of the Theatre of the Absurd” (p.498).

Insufferable as B is, as Greta Johnsen observes, he is sort of “charming,” because in addition to being really smart he intimates the presence of at least a soupçon of self-consciousness about his failings. “I make me sick,” (p.500) he admits between bouts of self-aggrandizement and free associative leaps of reasoning evincing a messiah complex that sits uneasily with his sexual preference for being dominated by strong women, Jewish, Black and otherwise, trans and natural. “If that strong woman happens to be African American, well, [B is] in heaven” (p.196). Does he contradict himself? Very well, then he contradicts himself. The very second sentence of the first paragraph identifies Whitman by name, while the first sentence extols B Rosenberger Rosenberg’s beard. Perhaps, he sees in each strand of his beard, in its Whitmanesque, Rasputinian, and Dawrinian family resemblance, “no less than the journey work of the stars.”

Though Johnsen is right to note that Antkind is an exercise in a sort of gematria of high and low culture signifiers, it is a stretch to think this a merit of this book of many merits. Bringing Hegel and Friends into an inchoate proximity in a gestalt governed ultimately by free association is, I submit, not as impressive as Slavoj Žižek’s bringing Hegel and anal sex into premises licensing analogical inferences about the nature of some psychological phenomenon. Žižek in setting out to educate his reader entertains only by accident, and this accident creates a happy normative situation where he deserves praise for performing a supererogatory service. It was only his job to teach, but now he’s also made us chuckle. Kaufman in setting out to entertain incurs an obligation to make us chuckle, or mope, or rage. But in presuming to educate us about the profound wickedness and frivolity in the hearts of the most benign and ineffectual of men, if unintentionally, he incurs a normative sanction for doing the aesthetically impermissible. It was only his job to make us feel stuff, and now he presumes to teach! It better be an entertaining lesson; so entertaining, in fact, we forget what is ostensibly being taught. Psychoanalytic theory, exposited by Žižek in the same ludic vein as Kaufman’s first-personal cogitations in Antkind, is committed not only to exploiting combinatorial possibilities of signifiers of the outré and the elite, high and low culture, but also to the limits the world sets on intelligible combinations of proper nouns occurring in paragraphs that are part of a single work. Engineering discussion of the phenomenology of anal and oral sex via glory holes into an exposition of Hegel and Lacan (Žižek 2020) is a different sort of achievement from depicting B as having had cartoon avian companions named Hegel and Schlegel. Here the names of the German idealists become empty signifiers, playing no other role in the plot but for making B appear to be as well-read as he is zany.

The unique strength of Kaufman’s writing at the level of craft is in his ability to flagrantly, and exhibitionistically, violate tenets of good writing propagated by MFA programs, Strunk and White partisans, and The New Yorker reading intelligentsia. One finds unironic use of nouns like “hebetudinousness” (p.295), adjectives like “pulchritudinous” (p.409) in passages which would not allow felicitous replacement by the bargain basement alternatives of stupidity and beautiful respectively. To rewrite such passages in a simpler diction, a less elevated register, would mangle and distort the authentic inner voice of B; making him appear less eccentric and more monstrous than he is. Part of his affliction, his failing as a person, consists in being a Frankenstein’s monster composed out of curious and ill matched traits. He is obviously of high intelligence, is incredibly well-read, knows eleven languages, did some math at Harvard, and is capable of making dinner party small talk on topics ranging from the block theory of the universe to the films of Tarantino. But he also has poor impulse control, low conscientiousness, covert and vulnerable narcissism, and has trouble understanding and respecting the personal space of others; especially women. He stalks his enigmatic love interest Tsai and insinuates himself into her life till she pulls the plug on this decidedly one sided romance. He is incredibly needy, and wants constant reassurances of love from his steady girlfriend; a famous sitcom actress of celebrity good looks, an African American woman whose race is nine tenths of her charm for B.

It is no doubt entertaining to see Kaufman’s nimble yarn recreate familiar naïve longings, like the one to have been the discoverer of the Americas instead of Amerigo Vespucci or having connected dreaming with wish fulfilment fantasies instead of Freud. B’s mind is a funhouse mirror in which the reader is invited to see himself as he might possibly, and in spite of himself, be. B’s thinking that someone came up with “Irony and Idealism: Rereading Schlegel, Hegel, and Kierkegaard” before he did with “Isn’t it Romantic? Idealism and Irony: Reexamining Hegel, Schlegel, and Kierkegaard” only because of “some sort of transfer of information from [his] brain to [theirs]” (p.522) is a cope. Even so, one treads a fine line between accusing Kaufman of bestowing his polymathic protagonist with a curiously stunted imagination and avoiding chastising Kaufman for B’s faults. The author is dead. Long live Kaufman! The principal weakness of this book is not qualitative, but formal; its writing is muscular and agile, but the ends it serves are so poorly defined as to defy encounter as an aesthetic object. One could write monographs and build a career around the vexed question of the means and ends of aesthetic objects, and even on the subspeciality of the Kaufmanian aesthetic object. Suffice it to say the narrative arc here is not as intelligible as it is in other Kaufman projects.

One can fairly reasonably summarize the webs of plots and subplots in Synecdoche, New York, Being John Malkovich, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind for instance. But even Kaufman admits he isn’t clear on which ambiguities need and admit of being given a concrete resolution if Antkind were to be adapted for film. This, I submit, is a flaw in Antkind in its capacity as a novel. Forget unfired Chekovian guns in the third act, once the twin Trunks have copulated Antkind’s narrative world undergoes such a severe deformation that it is nigh impossible to tell what role is being played by characters whose sayings and doings quickly come to dominate hundreds of passages. A lone sapient ant, called Calcium, a puppet created by Ingo has created a virus: time rabies, which is ravaging the world. Which world? We don’t know because Calcium time travels, as do other characters. Suffice it to say, if Calcium had tried to work out the logistics of using time rabies to fuel his jet to time travel back to B “it would take a great deal of time rabies fuel” (p.964).

Is this novel worth reading, and should you read it? These are questions a review is obligated to answer, though literary criticism might elide them. In advertising this piece as a review I am committed to answer. So, I’ll say it absolutely is worth reading. As to whether you should read it, it depends on whether or not: you are okay with reading words like hebetudinousness, and pulchritudinous in fiction; you are willing to let the central plot meander without resolution; you are fine with metafictional political and cultural commentary that is becoming stale even as you read this. This piece also is a small serving of literary criticism, and like Kaufman I think criticism ought to deliver more than a vote or veto. Accordingly, I’ve spent some time zooming in on aspects of Antkind’s modus operandi qua shaggy dog story, its use of free association, its formal innovation, and its literary register. If you come away thinking you’re likely to find this book to be deserving a 3.5 out of 5 then I’ll have succeeded in my project. That’s my rating in any case.